In 1962, my father participated in fair housing testing of a development benefiting from Federal Housing Administration financing.

Classic paired fair housing testing involves Black and white homeseekers inquiring at the same home or apartment, potentially learning that the seller or landlord will sell/rent to the latter but not the former. This practice was endorsed by the Supreme Court in 1982 in the case of Havens Realty Corp. v. Coleman, 455 U.S. 363, 374 (1982) holding that, in such situations, the Black tester had standing to sue the housing provider for discrimination. By 1982, however, at least some subtlety was required: in Havens, a Black tester inquired and was told no apartment was available; in a separate inquiry, a white tester was told there were vacancies. Id. at 368. In this way, non-obvious discrimination can be identified and challenged.

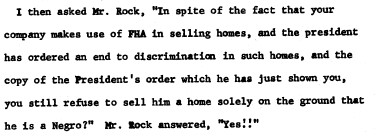

In 1962, when the Fair Housing Act was still six years in the future – and the relevant Executive Order hot off the presses – testing required no subtlety whatsoever. Below is a draft affidavit my father prepared detailing his role in a paired test.

STATEMENT BY PETER C. ROBERTSON TO SUPPORT COMPLAINT BY KARL D. GREGORY FILED WITH THE FEDERAL HOUSING ADMINISTRATION

I am Peter Robertson, [STREET ADDRESS REDACTED] Washington, 16, District of Columbia. On December 15, 1962 I accompanied Mr. Karl D. Gregory and his wife and child and Mr. Marvin Caplan in a visit to the Belair project of Levitt and Sons, Incorporated, at Bowie, Prince George’s County, Maryland. Mr. Gregory’s purpose in going to Belair was to purchase for the personal use of himself and his family a personal residence from those offered for sale by Levitt and Sons, Incorporated.

Upon arrival at the project Mr. Caplan and I went immediately to the sales office. Mr. and Mrs. Gregory and their daughter went to look at the model homes. When we arrived at the sales office we engaged in conversation one of the men standing behind the counter and appearing to be a salesman. We did not obtain his name. This salesman indicated in answer to our questioning that there were a number of houses available. He indicated that there were some available for short term delivery at reduced prices which had been quoted in an advertisement in the morning paper (Washington Post, 15 December 1962), and that there were a number of houses available for later delivery at the non-reduced prices. He further indicated that a potential buyer could be assured of obtaining financing insured by the Federal Housing Administration of the United States Government and thus a low down payment. In fact, he indicated to us that the prices which appeared in all of the published advertising issued by Levitt and Sons, Incorporated, were based on the assumption that the buyer will purchase the house with a mortgage insured by the Federal Housing Administration.

I had called on the telephone prior to going to Belair and had been given similar information over the telephone by the Levitt and Sons, Incorporated, salesman who spoke to me on the phone. Thus the low down payments which are offered by Levitt and Sons, Incorporated, both in person and over the telephone are possible only if such a mortgage insured by the Federal Housing Administration is obtained. A down payment more than four times as large is required if such insurance is not obtained. Thus does the participation of the Federal Government materially aid Levitt and Sons, Incorporated, in the sale of residential housing.

After Mr. Caplan and I had discussed the financing arrangements Mr. and Mrs. Gregory came into the sales office and Mr. Gregory indicated that he was interested in buying a home. The salesman, Mr. Herbert Rock, declined to give the Gregorys an application stating that it was against the policy of his company to “accept applications from Negroes.” Mr. Gregory then asked if the sole reason for not making the sale was that he was a Negro. Mr. Rock replied, “Yes.”

Mr. Gregory then asked Mr. Rock if he had read the Executive Order (11063) of the President of the United States prohibiting discrimination because of race in the sale of residential housing where such housing was financed, or where the financing was insured, by the Federal Government. The answer was to the effect that Mr. Rock had not read the order but that he assumed that Mr. Levitt had. Mr. Gregory then read Mr. Rock some parts of the executive order and then asked again, “Do you still refuse to sell me a home?” Answer, “Yes.” Then, “Do you still base this refusal solely on the fact that I am Negro.” Answer, “Yes.”

I then asked Mr. Rock, “In spite of the fact that your company makes use of FHA in selling homes, and the president has ordered an end to discrimination in such homes, and the copy of the President’s order which he has just shown you, you still refuse to sell him a home solely on the ground that he is a Negro?” Mr. Rock answered, “Yes!!” Mr. Gregory then requested to know the amount of the initial deposit that would be necessary for a potential white buyer to commence the processing of an application. Mr. Rock said that it took one hundred dollars. Thereupon, Mr. Gregory handed him some cash, Mr. Rock counted it and verified — at Mr. Gregory’s request — that there was, in fact, one hundred dollars. He refused to accept the money, however, repeating that a sale to a Negro was against the company’s policy. He handed the money back to Mr. Gregory and said. “Now you have your case.”

On several occasions in addition to those specifically cited above Mr. Rock explicitly said that he was refusing to sell a house to Mr. Gregory solely on the ground that Mr. Gregory was a Negro, and that he was acting on instructions which reflected the official policy of the company for which he worked.

I, Peter Robertson, [ADDRESS REDACTED] Washington 16, D.C., do hereby state that the foregoing is a true statement.

“Now you have your case.”

Levitt & Sons were the builders of the infamous Levittown and similar developments around the country. These development were made possible by FHA loan guarantees which, in the 1940s and 1950s required that each home have a restrictive covenant: a clause in the deed prohibiting resale to Black people. That’s right, our government mandated housing segregation in a program that created several generations of white family capital. (Richard Rothstein’s The Color of Law: A Forgotten History Of How Our Government Segregated America” is a brilliant account of this and similar programs.)

On November 20, 1962, President Kennedy issued Executive Order 11063, 27 Fed. Reg. 11527, prohibiting discrimination in federally-supported housing. My father’s test took place less than a month later.

Throughout the 28 years of our work at Fox & Robertson, my husband and I have had many occasions to work on civil rights testing issues, from Tim establishing the gold standard for Americans with Disabilities Act tester standing in the Ninth Circuit, to my work on a team defending the practice in an amicus brief to the Supreme Court. But I had learned about basic paired testing long before, from my father, around the dinner table (metaphorical dinner table – more likely on some early morning figure skating commute). My father admired the practice and later urged us to use it in our disability rights cases, which we did to excellent effect. Throughout it all, I had no idea he himself had been a tester.